. . . under the impetus of PARALLEL ROADS (23) and NETWORK OF PATHS AND CARS (52), paths will gradually grow at right angles to major roads - not along them as they do now. This is an entirely new kind of situation, and requires an entirely new physical treatment to make it work.

Where paths cross roads, the cars have power to frighten and subdue the people walking, even when the people walking have the legal right-of-way.

Therefore:

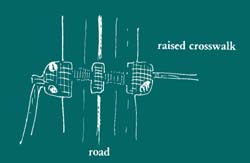

At any point where a pedestrian path crosses a road that has enough traffic to create more than a two second delay to people crossing, make a "knuckle" at the crossing: narrow the road to the width of the through lanes only; continue the pedestrian path through the crossing about a foot above the roadway; put in islands between lanes; slope the road up toward the crossing (1 in 6 maximum); mark the path with a canopy or shelter to make it visible.

This will happen whenever the path and the road are at the same level. No amount of painted white lines, crosswalks, traffic lights, button operated signals, ever quite manage to change the fact that a car weighs a ton or more, and will run over any pedestrian, unless the driver brakes. Most often the driver does brake. But everyone knows of enough occasions when brakes have failed, or drivers gone to sleep, to be perpetually wary and afraid.

The people who cross a road will only feel comfortable and safe if the road crossing is a physical obstruction, which physically guarantees that the cars must slow down and give way to pedestrians. In many places it is recognized by law that pedestrians have the right-of-way over automobiles. Yet at the crucial points where paths cross roads, the physical arrangement gives priority to cars. The road is continuous, smooth, and fast, interrupting the pedestrian walkway at the junctions. This continuous road surface actually implies that the car has the right-of-way.

What should crossings be like to accommodate the needs of the pedestriansP

The fact that pedestrians feel less vulnerable to cars when they are about 18 inches above them, is discussed in the next pattern RAISED WALK (55). The same principle applies, even more powerfully, where pedestrians have to cross a road. The pedestrians who cross must be extremely visible from the road. Cars should also be forced to slow down when they approach the crossing. If the pedestrian way crosses 6 to 12 inches above the roadway, and the roadway slopes up to it, this satisfies both requirements. A slope of 1 in 6, or less, is safe for cars and solid enough to slow them down. To make the crossing even easier to see from a distance and to give weight to the pedestrian's right to be there, the pedestrian path could be marked by a canopy at the edge of the road - CANVAS ROOFS (244).

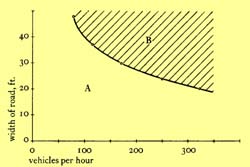

Go to the road in question several times, at different times of day. Each time you go, count the number of seconds you have to wait before you can cross the road. If the average of these waiting times is more than two seconds, then we recommend you use the pattern. (On the basis of Buchanan's statement that roads become threatening to pedestrians when the volume of traffic on them creates an average delay of two seconds or more, for people trying to cross on foot. See the extensive discussion, Colin Buchanan et al., Traffic in Towns,HMSO, London, 1963, pp.203-13.) If you cannot do this experiment, or the road is not yet built, you may be able to guess, by using the chart below. It shows which combinations of volume and width will typically create more than a two-second average delay.