. . . roads may be governed by PARALLEL ROADS (23), LOOPED LOCAL ROADS (49), GREEN STREETS (51); major paths by ACTIVITY NODES (30), PROMENADE (31),and PATHS AND GOALS (120). This pattern governs the interaction between the two.

Cars are dangerous to pedestrians; yet activities occur just where cars and pedestrians meet.

Therefore:

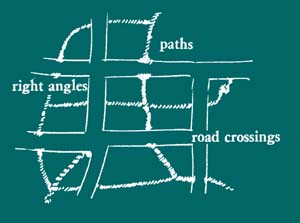

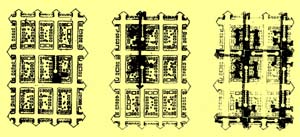

Except where traffic densities are very high or very low, lay out pedestrian paths at right angles to roads, not along them, so that the paths gradually begin to form a second network, distinct from the road system, and orthogonal to it. This can be done quite gradually - even if you put in one path at a time, but always put them in the middle of the "block," so that they run across the roads.

It is common planning practice to separate pedestrians and cars. This makes pedestrian areas more human and safer. However) this practice fails to take account of the fact that cars and pedestrians also need each other: and that, in fact, a great deal of urban life occurs at just the point where these two systems meet. Many of the greatest places in cities, Piccadilly Circus, Times Square, the Champs Elyse'es, are alive because they are at places where pedestrians and vehicles meet. New towns like Cumbcrnauld, in Scotland, where there is total separation between the two, seldom have the same sort of liveliness.

The same thing is true at the local residental scale. A great deal of everyday social life occurs where cars and pedestrians meet. In Lima, for example, the car is used as an extension of the house: men, especially, often sit in parked cars, near their houses, drinking beer and talking. And in one way or another, something like this happens everywhere. Conversation and discussion grow naturally around the lots where people wash their cars. Vendors set themselves up where cars and pedestrians meet; they need all the traffic they can get. Children play in parking lots-perhaps because they sense that this is the main point of arrival and departure; and of course because they like the cars. Yet, at the same time, it is essential to keep pedestrians separate from vehicles: to protect children and old people; to preserve the tranquility of pedestrian life.

Children like cars.

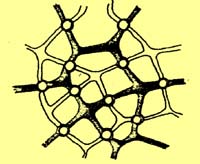

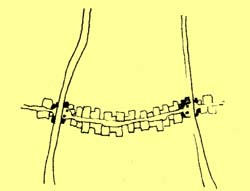

To resolve the conflict, it is necessary to find an arrangement of pedestrian paths and roads, so that the two are separate, but meet frequently, with the points where they meet recognized as focal points. In general, this requires two orthogonal networks, one for roads, one for paths, each connected and continuous, crossing at frequent intervals (our observations suggest that most points on the path network should be within 150 feet of the nearest road), meeting, when they meet, at right angles.

Children like cars.

To resolve the conflict, it is necessary to find an arrangement of pedestrian paths and roads, so that the two are separate, but meet frequently, with the points where they meet recognized as focal points. In general, this requires two orthogonal networks, one for roads, one for paths, each connected and continuous, crossing at frequent intervals (our observations suggest that most points on the path network should be within 150 feet of the nearest road), meeting, when they meet, at right angles.

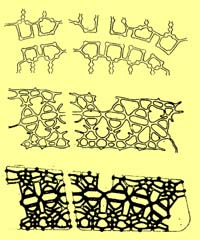

It can be done within the system of fast one-way roads about 300 feet apart described in PARALLEL ROADS (23). Between the roads there are pedestrian paths running at right angles to the roads, with buildings opening off the pedestrian paths. Where the paths intersect the roads there are small parking lots with space for kiosks and shops.

|

Roads. Pedestrian paths. The two together. |

Finally, note that this kind of separation of cars from pedestrians is only appropriate where traffic densities are medium or medium high. At low densities (for instance, a cul-de-sac gravel road serving half-a-dozen houses), the paths and roads can obviously be combined. There is no reason even to have sidewalks - GREEN STREETS (51). At very high densities, like the Champs Elyse'es, or Piccadilly Circus, a great deal of the excitement is actually created by the fact that pedestrian paths are running along the roads. In these cases the problem is best solved by extra wide sidewalks - RAISED WALKS (55) - which actually contain the resolution of the conflict in their width. The edge away from the road is safe - the edge near the road is the place where the activities happen.