If a teenager's place in the home does not reflect his need for a measure of independence, he will be locked in conflict with his family.

Therefore:

To mark a child's coming of age, transform his place in the home into a kind of cottage that expresses in a physical way the beginnings of independence. Keep the cottage attached to the home, but make it a distinctly visible bulge, far away from the master bedroom, with its own private entrance, perhaps its own roof.

In most family homes the rooms for children and adolescents are essentially the same. But when children become adolescents, their relationship to the family changes considerably. They become less and less dependent on the family; they take on greater responsibilities; their life outside the home becomes richer, more absorbing. Most of the time they want more independence; occasionally they really need the family to fall back on; sometimes they are terrified by the confusion within and around them. All of this places new demands on the organization of the family and, accordingly, on the organization of the house.

To really help a young person go through this time, home life must strike a subtle balance. It must offer tremendous opportunities for initiative and independence, as well as a constant sense of support, no matter what happens. But American family life never seems to strike this balance. The studies of adolescent family life depict a time of endless petty conflict, tyranny, delinquency, and acquiescence. As a social process, adolescence, it seems, is geared more to breaking the spirit of young boys and girls, than to helping them find themselves in the world. (See, for example, Jules Henry, Culture Against Man, New York: Random House, 1963.)

In physical terms these problems boil down to this. A teenager needs a place in the house that has more autonomy and character and is more a base for independent action than a child's bedroom or bed alcove. He needs a place from which he can come and go as he pleases, a place within which his privacy is respected. At the same time he needs the chance to establish a closeness with his family that is more mutual and less strictly dependent than ever before. What seems to be required is a cottage which, in its organization and location, strikes the balance between a new independence and new ties to the family.

The teenager's cottage might be made from the child's old bedroom, the boy and his father knocking a door through the wall and enlarging the room. It might be built from scratch, with the intention that it later serve as a workshop, or a place for grandfather to live out his life, or a room to rent. The cottage might even be an entirely detached structure in the garden, but in this case, a very strong connection to the main house is essential: perhaps a short covered path from the cottage into the main kitchen. Even in row housing, or apartments, it is possible to give teenagers rooms with private entry.

Is the idea of the teenage cottage acceptable to parents? Silverstein interviewed 12 mothers living in Foster City, a suburb of San Francisco, and asked them whether they would like a teenage cottage in their family. Their resistance to the idea revolved around three objections:

1. The cottage would be useful for only a few years, and would then stand empty.

2. The cottage would break up the family; it isolates the teenager.

3. It gives the teenager too much freedom in his comings and goings.

Silverstein then suggested three modifications, to meet these objections:

To meet the first objection, make the space double as a workshop, guest room, studio, place for grandmother; and build it with wood, so it can be modified easily with hand tools.

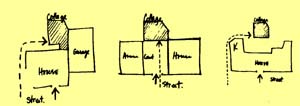

To meet the second objection, attach the cottage to the house, but with its own entrance; attach the cottage to the house via a short hall or vestibule or keep the cottage to the back of the lot, behind the house.

To meet the third objection, place the cottage so that the path from the room to the street passes through an important communal part of the house - the kitchen, a courtyard.

He discussed these modifications with the same twelve mothers. Eleven of the twelve now felt that the modified version had some merit, and was worth trying. This material is reported by Murray Silverstein, in "The Boy's Room: Twelve Mothers Respond to an Architectural Pattern," University of California, Department of Architecture, December 1967.

Here are some possible variants containing these modifications.

Variations of teenager's cottage.

Among the Comanches, ". . . the boy after puberty was given a separate tepee in which he slept, entertained his friends, and spent most of his time." (Abram Kardiner, Psychological Frontiers of Society, New York: Columbia University Press, 1945, p. 75.)

Plan of a Yungur Compound, Africa; 2 is the master bedroom; 3 is the daughter's hut; 4 is the son's hut.

And finally, from Simone De Beauvoir:

When I was twelve I had suffered through not having a private retreat of my own at home. Leafing through Mon Journal I had found a story about an English schoolgirl , and gazed enviously at the colored illustration portraying her room. There was a desk, and a divan, and shelves filled with books. Here, within these gaily painted walls, she read and worked and drank tea, with no one watching her - how envious I felt! For the first time ever I had glimpsed a more fortunate way of life than my own. And now, at long last, I too had a room to myself. My grandmother had stripped her drawing room of all its armchairs, occasional tables, and knickknacks. I had bought some unpainted furniture, and my sister had helped me to give it a coat of brown varnish. I had a table, two chairs, a large chest which served both as a seat and as a hold-all, shelves for my books. I papered the walls orange, and got a divan to match. From my fifth-floor balcony I looked out over the Lion of Belfort and the plane trees on the Rue Denfert-Rochereau. I kept myself warm with an evil-smelling kerosene stove. Somehow its stink seemed to protect my solitude, and I loved it. It was wonderful to be able to shut my door and keep my daily life free of other people's inquisitiveness. For a long time I remained indifferent to the decor of my surroundings. Possibly because of that picture in Mon Journal I preferred rooms that offered me a divan and bookshelves, but I was prepared to put up with any sort of retreat in a pinch. To have a door that I could shut was still the height of bliss for me . . . I was free to come and go as I pleased. I could get home with the milk, read in bed all night, sleep till midday, shut myself up for forty-eight hours at a stretch, or go out on the spur of the moment . . . my chief delight was in doing as I pleased. (Simone De Beauvoir, The Prime of Life, New York: Lancer Books, 1966, pp. 9-10.)

Arrange the cottage to contain a SITTING CIRCLE (185) and a BED ALCOVE (188) but not a private bath and kitchen - sharing these is essential: it allows the boy or girl to keep enough connection with the family. Make it a place that can eventually become a guest room, room to rent, workshop, and so on - ROOMS TO RENT (153), HOME WORKSHOP (157). If it is on an upper story, give it a separate private OPEN STAIR (158). And for the shape of the cottage and its construction, start with THE SHAPE OF INDOOR SPACE (191) and STRUCTURE FOLLOWS SOCIAL SPACES (205). . . .